On Visibility

“It’s not the world that is my oppressor, because what the world does to you, if the world does it to you long enough and effectively enough, you begin to do to yourself.” – James Baldwin

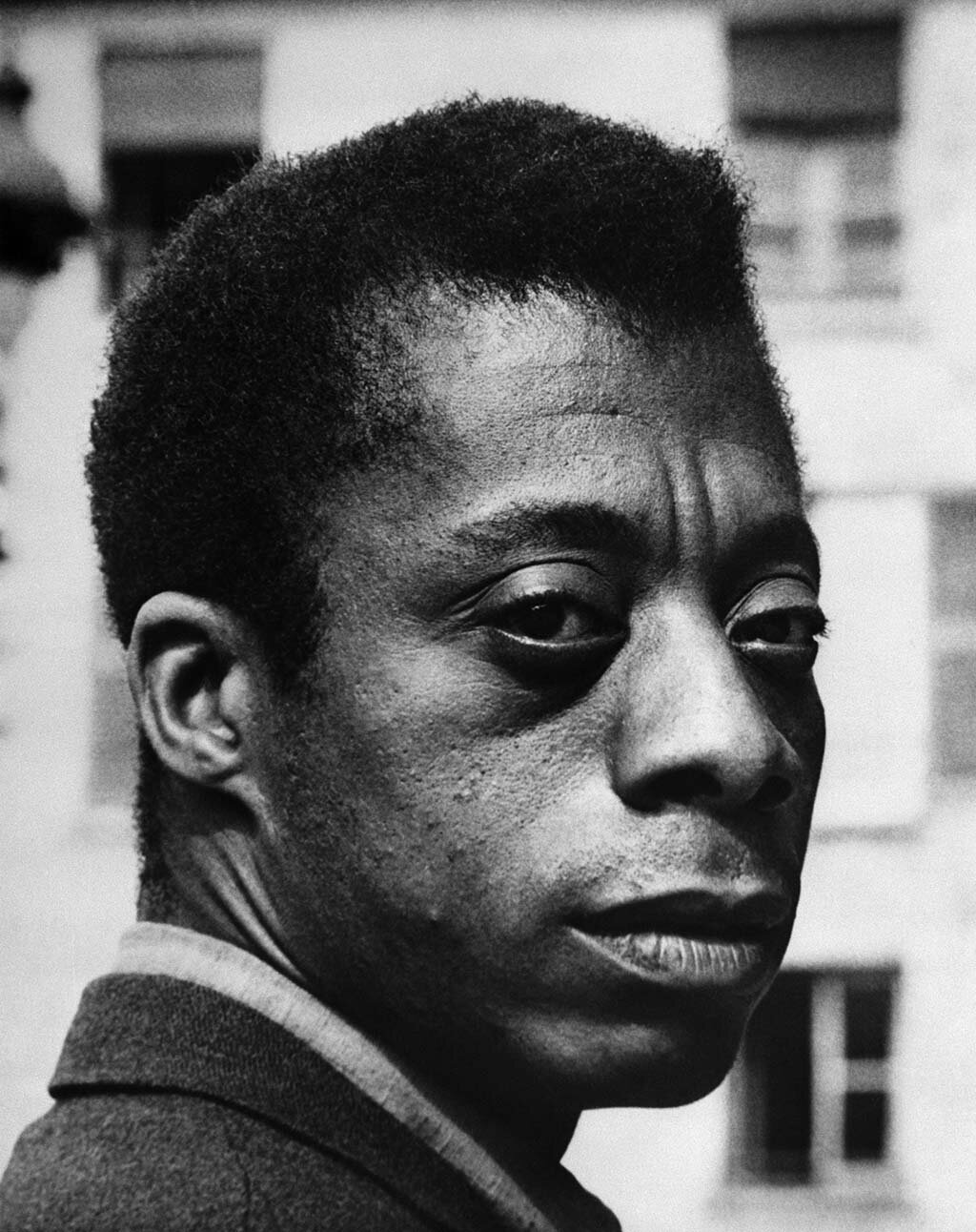

James Baldwin. Public domain image.

In 1971, writer James Baldwin and poet Nikki Giovanni sat together and had a conversation that explored various aspects of race and identity. It is from this conversation, titled A Dialogue, that the above quote is taken. Although Baldwin speaks specifically about the Black psyche, his words can be applied to the Asian American experience as well, considering what the Asian American community has dealt with since the beginning of the United States: from exclusionary immigration and citizenship practices, to the scapegoating of entire communities (Japanese, Chinese, Muslims and Sikhs) during times of international conflict, from the appropriation of our identities as tools for white supremacy through the model minority myth, to the capitalist appropriation of our cultures, from the homogenization and othering of our communities, and notably now to the racist hate crimes that continue to persist and have only soared since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the time of writing this (February 18th. 4:37 PM ET.), yet another anti-Asian attack has taken place. This time in New York City, where an unmasked white man shoved a 52-year-old Chinese American woman into the concrete so hard she hit her head and passed out. She needed stitches but is safe, the perpetrator since arrested by the NYPD. But collectively, the sense of unease still rises. I am afraid for my mother whenever she leaves the house. She has brown skin and black hair; she was already always a target. But my fear has escalated since. After all, she has Chinese blood.

It is not a secret that we have seen a stark rise in anti-Asian crime. With China as the West’s scapegoat for the pandemic, ethnically Chinese people – and anybody that can ‘plausibly pass’ as Chinese – will be forced to face the associated consequences. The harmful and racist rhetoric of highly visible individuals, however undeserving of their platform they may be, will always have tangible results. Harmful ones. Often deadly.

Though the escalation of anti-Asian hate crimes is very real, it is also true that we notice these occurrences so much more now. The dissemination of security cameras, digital and social media, and smartphones enable evidence of such crimes to be recorded so easily. We have higher visibility of white supremacist acts. This technology is a privilege. In this sense, visibility can be a privilege.

At the same time, I hesitate to consider visibility as a privilege. This topic is a common response to anti-Asian crime – that the country does not care enough about Asian Americans, that the media does not care enough about Asian Americans, because such crimes do not fall under the expected binary of White versus Black. But this is such a terribly ill-informed take to have, because BIPOC are already visible in that they physically embody nonwhiteness. And while it could be true that the media more often reports on anti-Black crime (a data study I would like to see but do not have the technical capabilities for), visibility is not a privilege. It is a default state of being for BIPOC, and one that extends to the violence and death experienced by Black bodies, a traumatic reminder to Black Americans that their lives are endangered simply because of their skin color. I could argue that the hypervisibility of the deaths of Black people by the State, while an effective mechanism for solidarity, is used also by white media to instill fear and thus inaction in those within shared communities. Conversely, the invisibility of American Indigenous people is intentional, a state of being constructed by white supremacy so that generations of citizens will neither remember nor recognize the extent of genocidal violence perpetrated by the State on an entire group of people who continue to resist yet are little visible.

When thinking about the politics of visibility, I am always immediately reminded of my own pale skin, pink tinted. Ambiguous facial features. Hair that is undeniably brown. I am grateful for this passing, for it allows me to become (in)visible. Then I think again to my mother and how she will never be afforded that same privilege. And it is through this train of thought that I wonder if similar sentiments are shared amongst others within the Asian American community. Some of us are (in)visible. When the War on Terror and 9/11 brought a surge of Islamophobia and anti-Muslim hate crimes to the West, it was South and West Asian Americans who suffered, those with brown skin, or those who were visibly Muslim or Sikh. Those who fell outside of this physical boundary were safe. For a time, they were (in)visible. But we see today that that notion of visibility, or lack of, is a falsehood. You are invisible only when white supremacy allows. Otherwise, if you lack a white body, if you practice a nonwhite culture, if you dare to go against the identity that whiteness has prescribed to you, you are forever visible.

And so I return to Baldwin’s quote. A frequent response to these crimes is the call for increased police presence by both Asian Americans and non-Asian Americans alike. A shared belief that more police will deter perpetrators from harming potential victims, that the lone elderly Asian person will be safer if their public outing is fenced by uniformed watchdogs. But what of racism within the police?

2020 brought the resurgence of discussions about the actual role of police (speaking of ‘police’ as an institution) within BIPOC communities. At surface level, police presence can deter criminal acts. But we also know that police are very distinctly a white supremacist invention, an easily weaponizable function to control a targeted community. In the immediate term, more police might mean that the lone elderly Asian person can walk to and from the convenience store safely. But as time goes on, what about others who walk down that same street? Asian Americans are not exempt from police brutality or misconduct – Kuanchung Kao, Tommy Le, and Angelo Quinto come to mind. Why are we calling for tools that serve to oppress us?

In this sense, Baldwin is right. We have been oppressed so effectively that we unknowingly seek to become the oppressor. We have internalized our own oppression, and the visibility of our bodies as we call for tools that harm our own will only embolden white supremacy to exploit us for its own preservation.

There is, however, a silver lining that is showing up as a response to these recent anti-Asian crimes. Community-based methods of safety are being practiced, such as the hundreds of individuals spanning generational and ethnic lines volunteering to escort elderly Asian people in Oakland, California, after the surge of Bay Area attacks. A community-focused and resourced practical solution to promote the safety of some members without jeopardizing the safety of others. A small proof that there exist working solutions for policing alternatives that can keep all members of a community safe, even during the wake of targeted violence. I would like to hold onto this optimism.

“Because we’re not obliged to accept the world’s definitions…we have to make our own definitions and begin to rule the world that way, because kids white and black cannot use what they have been given. It’s a very mysterious endeavor, isn’t it? And the key is love.” – James Baldwin