Reversing Jim Crow: Today’s Anti-Racism Laws and How They Can Be Improved

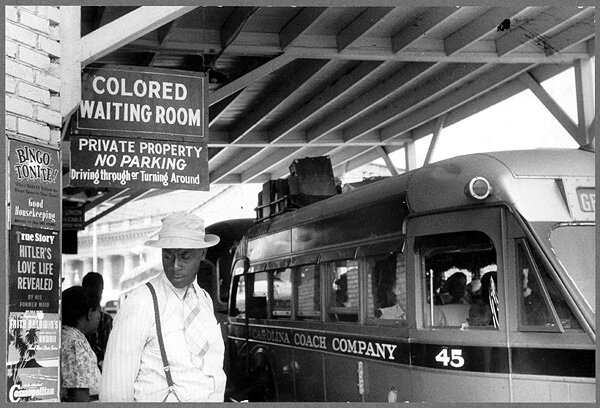

“At the bus station.” Jack Delano, photographer.

Durham, North Carolina. May 1940. Image retrieved from the Library of Congress.

She looked up at the white man in front of her. However, she didn’t move, didn’t change seats, and didn’t fulfill the white bus driver’s request to do so, knowing full well that what she was doing was illegal. In 1955, black people in Montgomery were required to give up their seats in the back of the bus when white people no longer had available seats in the front. As a result of this Jim Crow law, Rosa Parks was arrested for her noncompliance, spurring a year-long bus boycott that eventually desegregated buses in Alabama and Montgomery with the U.S. Supreme Court’s repeal of this law. However, this law wasn’t the only Jim Crow law of its time. A Jim Crow law was any law formed by bitter Southerners after losing the Civil War intended to legalize racial apartheid and segregation. Examples of Jim Crow laws included the construction of “whites only” restaurants, water fountains, bathrooms, cemeteries, parks, movie theaters, and schools and separate facilities for black people. However, even today, after all Jim Crow laws have been repealed and anti-discrimination laws have been enacted, not everyone experiences equal treatment and has equal access to services on the basis of their skin color. This disparity needs to be narrowed and ultimately eliminated.

Ruby Bridges. Image retrieved from the National Women’s History Museum.

Bravely walking past adults and even children holding signs with the words “We Want To Keep Our School White” in red and a coffin holding a black baby doll, 6-year-old Ruby Bridges was the first black child to desegregate the all-white William Frantz Elementary School in Louisiana in 1960, causing all except one of the teachers to quit and her classmates to change rooms. In the end, Ruby was taught by that one teacher who stayed and didn’t have any classmates for the rest of the year, demonstrating how even as the Jim Crow laws were being struck down, racism changed the way this student attended school. She didn’t even eat unsealed food because of threats of poison.

Today, our schools work under the Equal Educational Opportunities Act that prohibits public schools and their staff from discriminating against students on the basis of race, color, or nationality. While this law definitely reflects tolerance more than our nation’s laws once did, this isn’t enough. Black students still have obstacles that hinder their learning in schools and success later in life, such as the school-to-prison pipeline. Criminalizing certain rule-breaks with “zero-tolerance” policies and instituting police officers on campus who become involved in situations that could have easily been dealt with by the school, the school-to-prison pipeline is responsible for black students being suspended and expelled 3 times more often than white students, making them 3 times more likely to be involved with the juvenile justice system the following year. Additionally, even though black students only make up 16% of public school enrollment, they make up a disproportionate 31% of school-related arrests, demonstrating how this pipeline is cutting their education and futures short. On top of black students facing harsher discipline than their white peers, they also have to face anti-black microaggressions and racism from their classmates and even teachers on a regular basis. For example, some teachers unjustly set low expectations for black students and then act surprised when they excel academically.

In October 1960 in Louisiana, not only were black people not allowed to rent a building that was inhabited by a white people and vice versa, but any person who allowed this situation to happen would be fined no less than $25,000 or jailed for no less than 10 days. This racial segregation in housing was present throughout the South, seeking to prejudicially prevent cohabitance between black and white people. Since then, this housing law has been reversed with the Fair Housing Act, a law banning renters and sellers from discriminating against prospective renters and buyers on the basis of race, skin color, nationality, religion, sex, familial status, and/or disability, implemented by the Obama administration. However, it hasn’t prevented inequality from existing in housing. Gentrification, the movement of high-income people into low-income neighborhoods, forces low-income people out of their homes as a result of skyrocketing prices. Additionally, it causes housing to be less affordable, which poses an issue for the black community because as a result of systemic racism, they have a higher chance of needing this affordable housing and of being harmed by this discriminatory process.

“A street scene near the bus station.” Jack Delano, photographer.

Durham, North Carolina. May 1940. Image retrieved from the Library of Congress.

At least 12 black people, after being denied entrance into whites-only hospitals with white medical professionals, died in 1952. When hospitals were segregated by Jim Crow laws in the 1960s, the hospitals black people were allowed to seek treatment from lacked enough doctors, money, and equipment to treat people effectively. In 1965, hospital segregation was banned, and recently, the Anti-Racism in Public Health Act of 2020 was passed, adding a National Center for Anti-Racism and a Law Enforcement Violence Prevention Program (as a part of their injury prevention initiatives) to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Nevertheless, we need more. Black people, as a result of false, harmful, and ignorant beliefs that they can withstand more pain than white people can, have been refused treatments, tests, and diagnoses by their doctors. In particular, black women have faced the brunt of these life-threatening dismissals, being less likely than white people demonstrating the same symptoms to receive a prescription for painkillers from an ER physician and being 243% more likely than white women to die as a result of childbirth. While the more research that would occur through the National Center for Anti-Racism is important, we also need action in order to prevent more avoidable deaths of black people.

It’s undeniable that our laws regarding race have improved since 1960, moving from the wrong side of history to the right one. However, there’s still more progress than can be made. Black students shouldn’t have to take racist remarks from teachers. Low-income black families shouldn’t have to leave their neighborhoods. Black women shouldn’t be refused the pain medication they need. Our laws can fix this through instituting more rigid restrictions on discrimination, taking steps to start the dismantling of systemic racism. However, these laws won’t just magically come to fruition on their own. We need to speak up, writing and signing petitions, calling our representatives, and even proposing these bills on our own to small or overarching legislatures. We owe it to black people, during Black History Month and all year-round, to fight for the laws and protections they deserve.