Queer Joy in Undertale

Though it was only seven years ago, 2015 feels like a wildly different time to me. At seventeen years old, my understanding of the world back then was greatly informed by my Catholic education, and my years spent on websites like Tumblr—the one place where I could read and participate in candid conversations about race, gender, and sexuality, before the rest of my offline world seemed to catch on. Though 2015 predated our current cultural understanding of gender and “pronouns” being as commonplace as it is now, it was also the year same-sex marriage was legalized across the U.S. in Obergefell v. Hodges. As LGBTQ+ people became more visible in the world around us, they appeared more in our media, too—even video games.

On September 15, 2015, the indie game Undertale was released, and I think it might just be one of the first pieces of media featuring LGBTQ+ characters, relationships, and storylines that I ever experienced.

(Source: Game Maker)

Created by Toby Fox, Undertale is a story-driven game that follows a protagonist who ventures through an underground world inhabited by monsters who were banished to the Underground by humans. The protagonist must reach the end of the Underground to return to Earth’s surface, and they face countless encounters and battles with monsters along the way. The game is most famously known for emphasizing the consequences of players’ real-life ability to choose what to do in video games: you can play through the game killing every monster, or you can find ways to peacefully defeat every monster without harming them. When playing by the latter method, the player achieves the “true” ending to the story, in which the protagonist and all the monsters are freed from the Underground, so everybody wins. Undertale received wide critical acclaim and sold an unprecedented 1 million copies within the first six months of its release.

With Undertale came a massive online fandom. From my own personal experience consuming fan made Undertale content on Tumblr, YouTube, and fanfiction website Archive of Our Own, the majority of fans I encountered were queer adolescents, just like myself—many drawn to the game for its creative approach to storytelling, unique characters, and positive queer representation.

For all the choices players can make in this game, including naming the protagonist, players are never given the option to select a gender; throughout the game, the protagonist is only referred to with they/them pronouns. Many players have interpreted the protagonist to be “gender neutral” so players of any gender identity can see themselves in the protagonist, while others have interpreted the protagonist to be non-binary. For my teenage self, this was my first major exposure to a person using they/them pronouns, rather than she/her or he/him, and probably my first time fully comprehending what “non-binary” means.

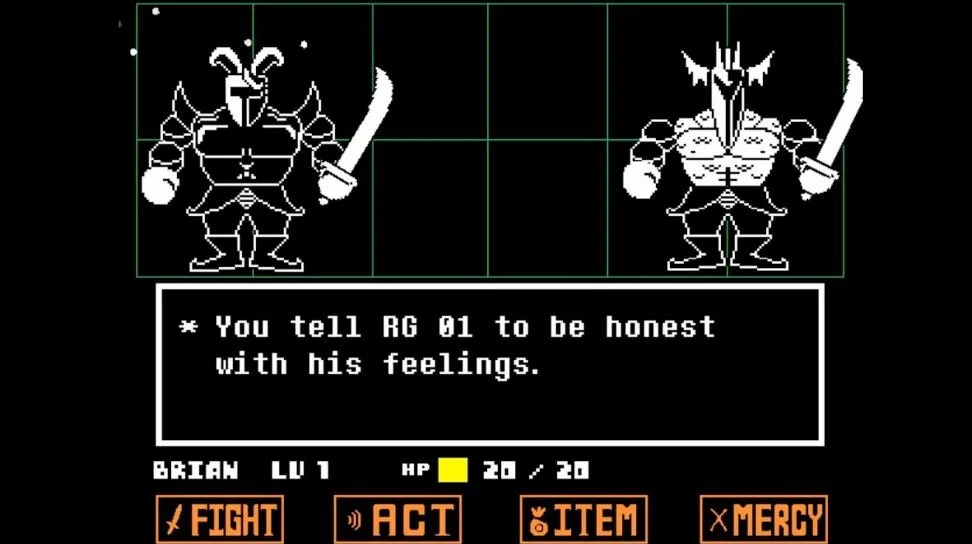

There are several moments in the game where cultivating queer joy is positioned as a required step to move the story forward. For example, when the player encounters two male royal guard monsters, the only way to defeat them without harming them is to encourage them to admit their longtime love for each other.

The player can encourage these two male royal guards to confess their love for each other, which is the only way to advance this part of the story without violence. (Source: YouTube)

Another prominent example that is required for completing the “pacifist route”—the fandom’s name for playing the game without killing anyone and thus achieving the story’s true ending—is the player helping the major character Alphys confess her feelings for Undyne, another major, female character. Shortly afterwards, Alphys and Undyne enter a relationship.

After the player encourages Alphys to confess her feelings to Undyne, Undyne embraces Alphys. They’re later confirmed to be in a relationship at the end of the game. (Source: Blogspot)

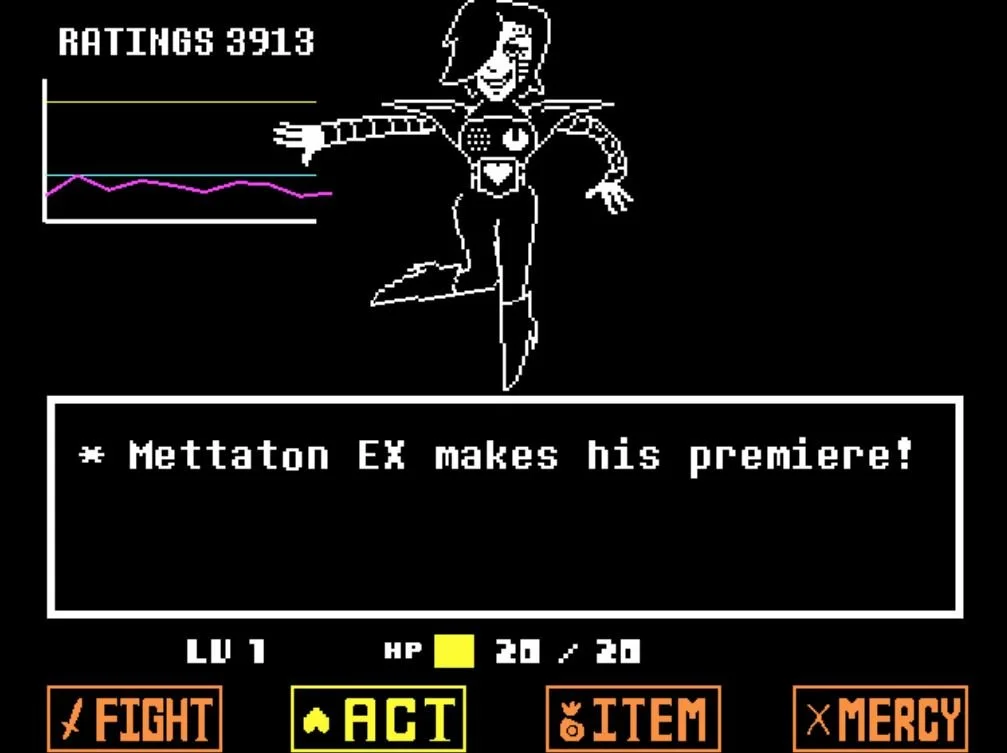

In addition to these relationships, there are other story events featuring positive queer representation that the player must trigger to finish the pacifist route. The game has several “dating simulator” sequences where the player goes on “dates” (though they usually end up being platonic) with both male and female characters. These sequences are often fun and silly, while showing the player more vulnerable sides to the characters, such as Alphys having a secret crush on Undyne. Another major character, Mettaton, who is a robot and identifies as male, takes on a more feminine robot body during a boss battle against him, in which he can be seen voguing—a style of dance that originated within the Black queer community in Harlem, as showcased in the documentary Paris is Burning (1990). Many fans interpret Mettaton as queer because of this battle. Despite it being a moment of conflict between the protagonist and Mettaton, it’s clear that Mettaton enjoys himself and feels much more comfortable in his new skin as the battle progresses.

The boss battle with Mettaton, as he debuts his new, more feminine body. (Source: Undertale Wiki)

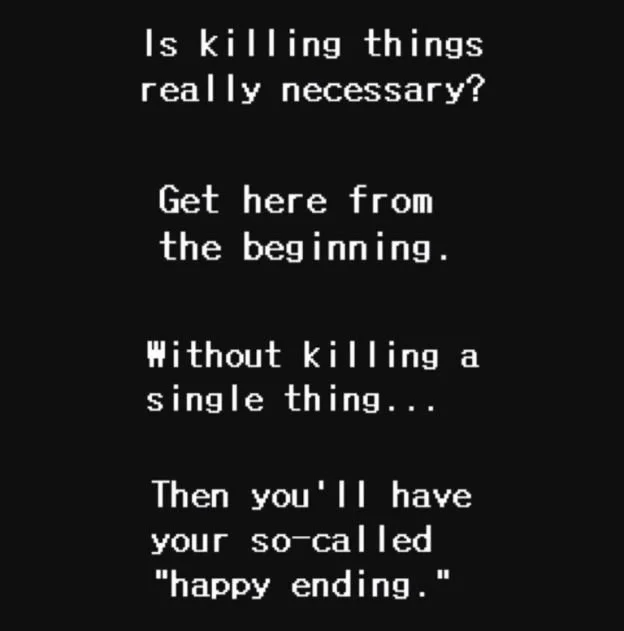

Though there are multiple ways a player can “beat” Undertale without triggering these story events, the game makes it clear that one gameplay route stands out as having the true ending intended by the creator, going so far as to break the fourth wall to blatantly encourage the player to restart and play the game without killing anyone to achieve a “happy ending.”

If the player kills monsters during their playthrough, a character gives the player this advice at the end of the game, instructing them to play again in a specific way. (Source: Undertale)

Because of this, I’d argue that queer joy is not just an optional aspect of Undertale, but a requirement to win the game. And when this true ending is achieved, the world becomes a utopia for all the characters: the protagonist and the monsters are freed from the Underground together, and they all begin a new life in community with humans on the surface. We can even view the plight of the monsters as symbolism for the experiences of many LGBTQ+ people: our community has been forced into the shadows, into secret and underground communities, for centuries, but when we can live freely and safely as ourselves, in community with all others, we can all achieve a “true” or happy ending for everyone.

When I first encountered Undertale, I hadn’t fully realized I was queer yet. I knew I felt differently from many of my peers, but I didn’t have the words or understanding to even comprehend my true self. Undertale was the first of several media I interacted with during that time of my life that inevitably set me on a path to self-discovery and working toward my own “true” ending, and for that, I will always be grateful.