derealization in a dissociative time

It was hell week in our school’s production of Pippin. I had never dedicated so much time and energy to a creative, collaborative endeavor. It finally felt like I was doing something I truly loved with people who drove me to do my best, who believed in me. And so, I gave my lowly ensemble role everything I had in me.

But then closing night was over, and I crashed the second I got home. I was awoken the next morning by my dad, who cautioned, “you’re going to be late for school.”

“But it’s Sunday,” I muffled into my pillow angrily.

“No... it’s Tuesday,” my dad said, concerned.

I turned on my phone to check if it were true. And it was. It was Tuesday.

When I stumbled out of bed, I got goosebumps. My tongue felt heavy in my mouth. My entire body ached. I told my parents how I felt, and they said I was completely fine yesterday. They said I had gone to school and everything.

“But yesterday was closing night?” I reasoned.

I didn’t remember going to school on Monday, or church on Sunday. Or rather, I was convinced the occurrences that took place on those days were dreams. There was no way they could have been real. All I could recollect was interactions I had with people, and even then, when looking back, it felt like I had no control over what I was saying to them.

My parents took me to urgent care, going off what I had told them about my physical symptoms. After running blood and urine tests, the doctors concluded I had a “virus” and just needed to get rest and drink plenty of fluids. So, that week, I stayed home and rested up.

Two years later, I came across a video one of my favorite artists, Dodie, had put out. I watched, listened to, and read everything and anything she released. In this video, she described exactly what I felt the following weeks after Pippin’s hell week. “I was kind of carrying stuff around with me, and around this time, I realized I had this uncomfortable sense of floating—not taking in as much as I used to, not being able to see properly, my memory being really bad…,” she explained, introducing the term derealization to my vocabulary. Was this what I dealt with in eighth grade?

In an interview, the Bio-Behavioral Institute’s Executive Director, Dr. Fugen Neziroglu stated that 50 to 70 percent of people will experience derealization or depersonalization at some point in their lives.

“Experiencing depersonalization or derealization doesn’t mean you have a disorder. Depersonalization and derealization disorders involve a persistent or recurring feeling of being detached from one’s body or mental processes,” said Dr. Neziroglu.

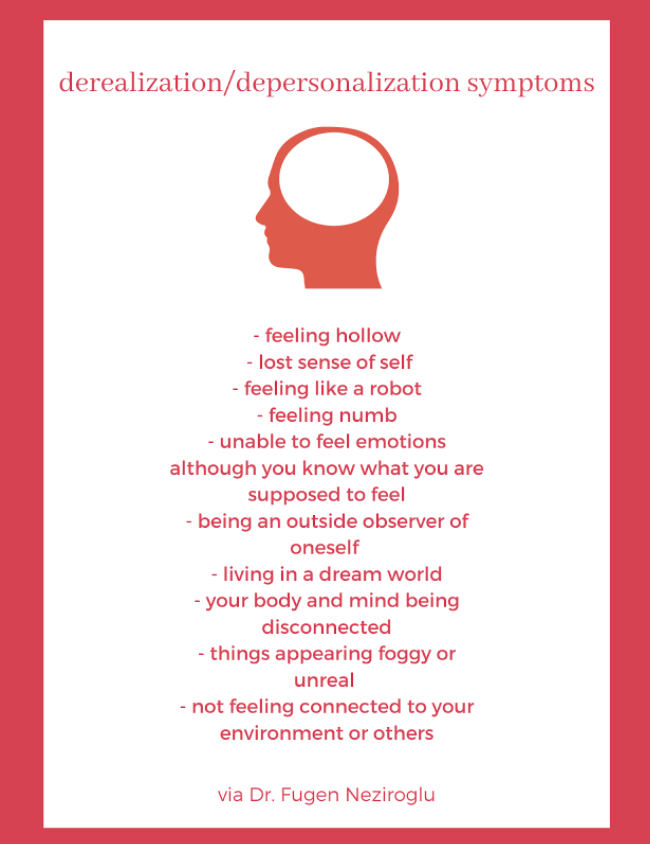

Depersonalization is identified with feelings of being detached from one’s body, whereas derealization refers to the feeling of being detached from one’s surroundings, according to Dr. Neziroglu. Because I identify with the latter, I asked her to further her delve into the feelings that derealization entails. But little did I know, depersonalization and derealization exhibit similar symptoms.

She proceeded to list all the possible feelings associated with the two mental states.

“Although we do not know what causes derealization we know what are common triggers. Often, a trauma that one lives through or remembers may trigger it, such as remembering chaos in your household as a child, or being physically or sexually abused. A very common trigger is marijuana, and even a one time usage of illicit drugs. Severe anxiety may also trigger it,” explained Dr. Nezigrolu.

She then discussed how fighting the feeling typically makes the sensation worse. Upon my own discovery of the mental state, I did exactly that.

My sophomore-aged self digested the information I’d learned from dodie and buried it in the depths of my brain until junior year came around, when I was talking to my dear friend Jamilah W., with whom I normally conversed about mental health. Dodie’s concept of derealization had been tossed around in our conversations before. I told her about this disconnect from reality I was feeling—this feeling of wanting to experience life like I once did, but not having the ability to do so because my perception felt so foggy and blurred. It constantly felt like I had just walked out of watching a two-hour long movie in theatres, and I needed a few minutes to ground myself back into reality. That was when I realized I dealt with derealization on a regular basis. Jamilah found that she’s struggled with it, too. Ever since, we’ve been checking in with one another on an almost-daily basis about how our mental and emotional states are.

“I feel like I found out what it was after I had been dealing with it for a while… I think it’s closely tied into when I was first experiencing anxiety, and even more so when I had to juggle work and school in my later high school years,” Jamilah explained.

Because Jamilah and I were so in-tune with discovering the reasoning behind our mental states, she did her own research on derealization to find that she exhibited a lot of the typical symptoms. She expanded on how initially, she would be present in her panic attacks, and then suddenly she’d have to remind herself where she worked, where she was, and who she was. That’s when the derealization creeped in.

“It’s weird to explain because it wasn’t that I was forgetting, it’s more that I was in such a state of panic that I had to remind myself of things that I knew to be true to bring me back down to reality,” she recounted.

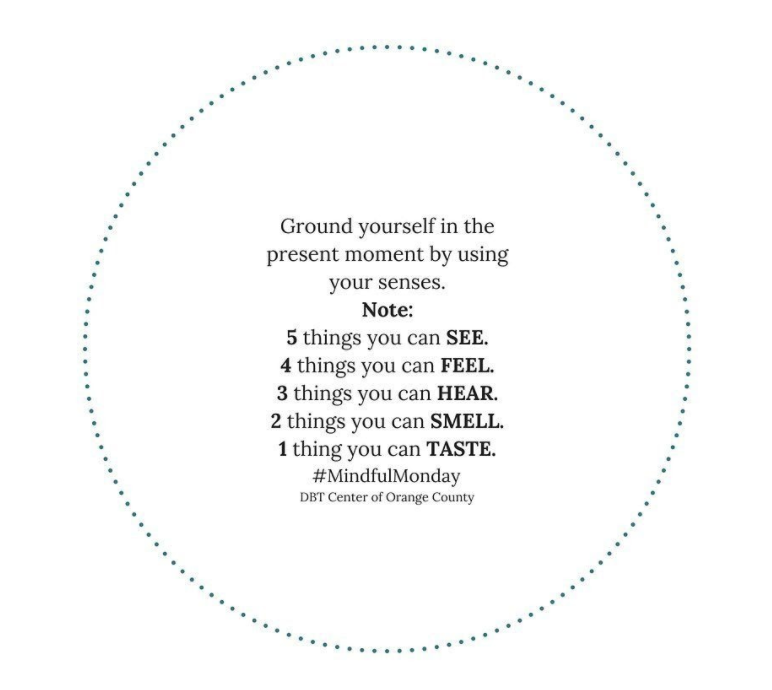

We then fell down a rabbit hole of discussing how niche derealization felt in comparison to other manifestations of panic and anxiety attacks. Because derealization isn’t something people talk about often, it’s easy to mistake misdiagnoses and self-diagnoses with actually experiencing symptoms on a WebMD page. A while back, when I was going through a really intense state of derealization, Jamilah sent me a list of five steps to follow to help ground myself.

Naturally, I wanted Dr. Neziroglu’s input on how to deal with derealization. She explained how the sensation is a difficult one to live with, but ultimately, trying to will it away won’t do anyone any good. “It is best to continue to engage in life even if you no longer have the same sensations, perceptions or feelings,” said Neziroglu.

But in a time of crisis, isolation, and prolonged stress, it is easier than usual to slip into a sense of hopelessness—whether that manifests as a pit of depression, increased occurrences of anxiety attacks, or a state of derealization. While we may not be able to control what’s going on in the world around us or the inner workings and chemical makeup of our own brains, we can practice identifying our needs and emotions, prioritizing treating ourselves with kindness. Because derealization and depersonalization specifically stem from feelings of disconnectedness, it is vital now more than ever to regularly check in with ourselves, check in with loved ones, prioritize human interaction (via the internet, of course. Social distance!), and ensure that we’re constantly working toward becoming more in-tune with our minds and emotions.

To find out more about derealization, see the WebMD description here. If you believe you may be dealing with derealization, you can take a self-assessment quiz via the Bio-Behavioral Institute. For more information about diagnoses and treatment options, visit Smart TMS’s informational page here.