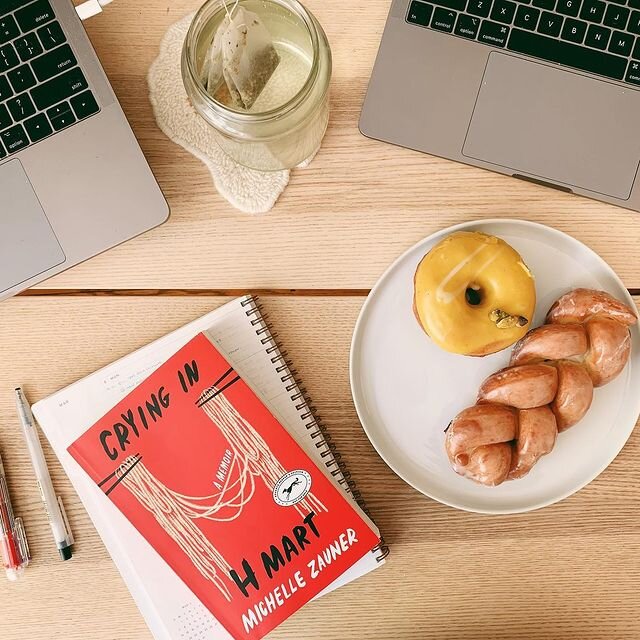

This is how many times I cried reading Michelle Zauner’s Crying in H Mart: A Book Review

Photo Credit: Giaae Kwon IG @jjoongie

Back in 2018, while doing something but not something important enough for me to remember, I found myself reading a free article on The New York Times. This article, a <5 minute read that left me a blubbery mess by its end, was the prequel to Zauner’s 2021 memoir of the same name, Crying in H Mart. Considering how much I could relate to the NYT piece – I’m sure I’m not alone in admitting that I am deathly afraid of losing my mom, my best friend and also the physical embodiment of my connection to Thai culture – as soon as I discovered that Zauner was expanding her piece into a whole book, I hopped onto Penguin Random House to place my preorder.

Boy, how I have never made a more validating purchase.

The day I received the book, I read it in one sitting, in the same chair for hours and only getting up to grab more tissues when my shirt was no longer a usable substitute. Zauner’s writing flows easily, indicative of her lifelong career as a musician. Despite taking liberal jumps back and forth in her history, the reader stays enraptured enough to never become lost, and the jumping helps to prepare us as we, together with her past self, approach the known inevitable – her mother’s untimely death after a long and embittered battle with cancer. Peppered throughout the pages, detailed descriptions of her family’s collective love affair with food, which serve to help us comprehend the extent of food’s power in bringing people together in times of both great happiness and grief.

“Something that was always in the hands of other people to be given and never my own to take, to decide which side I was on, whom I was allowed to align with. I could never be of both worlds, only half in and half out, waiting to be ejected at will by someone with greater claim than me.”

One white parent, one Asian. A dissonant experience that Zauner, who is half white and half Korean, describes with care and attentiveness: being othered by those whose culture, language, and food you share; being not quite the same; being the only half Asian, half white kid in your school; being Asian but also not Asian enough; being too much of one thing sometimes and too much of neither at all other times. All this paired with the dissonance from trying to relate to your own parents, a concept that Zauner explores equally at length for both her mother and father: her overwhelming desire to be a good daughter, at the risk of sacrificing her own desires and energy; how external criticism and validation was only impactful if it came from her mom, whose opinion she idolized above all others; her acknowledgement that her mother was truly the only connection tying herself to her dad and that without her, their relationship was ready and able to falter.

“My mother had struggled to understand me just as I struggled to understand her. Thrown as we were on opposite sides of a fault line – generational, cultural, linguistic – we wandered lost without a reference point, each of us unintelligible to each other’s expectations, until these past few years when we had just begun to unlock the mystery, carve the psychic space to accommodate each other, appreciate the differences between us, linger in our refracted commonalities. Then, what would have been the most fruitful years of understanding were violently cut short, and I was left alone to decipher the secrets of inheritance without its key.”

Ultimately, I am left with a profound feeling of gratitude towards Zauner, who traversed a journey – the loss of her mother, a loss made even more cruel by the onset of an inexcusably tragic disease – then so eloquently articulated the nuanced fear and grief that mixed-race people possess, so that when the inevitable loss happens to us too, we can at least be comforted in knowing we are not alone. Zauner succeeded also in encouraging her readers, mixed-race or not, to explore, amend, and deepen our relationships with our own parents, for that inevitable may show up more quickly than expected.

Out of the 239-page book, a total of 38 pages (approximately 16 percent) made me cry. To be fair, I was essentially crying continuously throughout the entirety of the book, but some sentences were a little more effective than others at bringing fresh tears to my eyes. These pages are listed below so that perhaps you may be a little more prepared.

6, 8, 10, 10, 11, 18, 33, 37, 42, 48, 69, 86, 91, 94, 117, 124, 127, 129, 136, 141, 143, 144, 146, 152, 154-157, 159, 160, 166, 186, 200, 223, 224, 226, 232, 239

Please, keep the tissues in reach.