Xenophobia and the Coronavirus: How the Outbreak has Radicalised Views on Race

via: Ashyka Chan

INSTAGRAM: @ashykachan

In light of the novel coronavirus pandemic and the increased xenophobia that has consequently ensued, I wanted to voice out a couple of thoughts that should be reinforced because of their urgency. As the coronavirus spreads, so too does the proportion of racist sentiment towards the global Asian community. A Singaporean student from UCL was assaulted on Oxford Street. An Asian American family, with a two-year old child, was held at knifepoint in Texas. Asian-Americans are concerned for their safety with President Trump’s labelling of Covid-19 as the ‘Chinese Virus’, spurring further tension alongside unnecessary marginalisation. The worst part is, all of these only reflect a handful of incidents out of the countless which have taken place more generally.

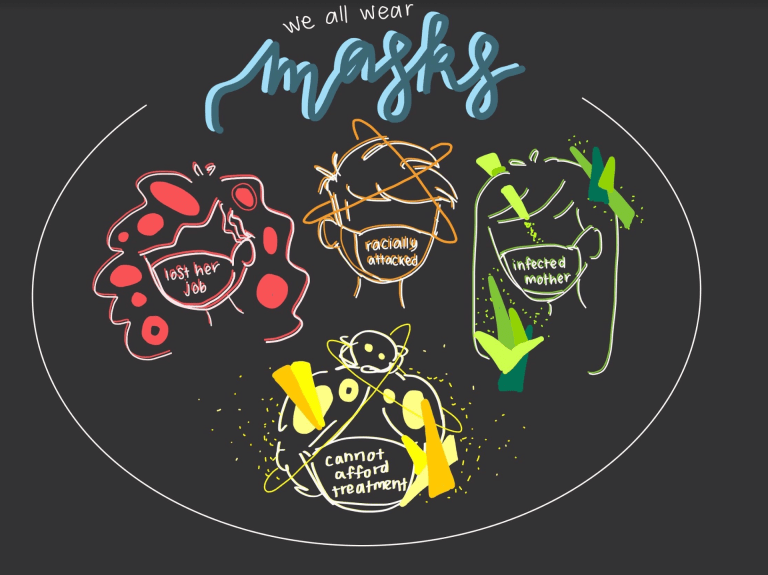

From verbal attacks to direct physical conflict, these incidents, from very different parts of the world, all have a basic overarching similarity. This is a misconception of fear, which has been used to sustain a violation of human right. It is extremely alarming that these matters are not being taken more seriously, especially when individuals who appear to be ‘Chinese’ or who wear masks are being justified as scapegoats for the wider public’s frustrations. It is important to address these problems in a global context as they reflect normalised or ingrained perceptions of ‘the other’ in our society which is recurrently brushed off. I want to bring attention to the mass hysteria which has ensued, to challenge unfair assumptions of what some people think is acceptable. There is a difference between spreading fact and fiction, especially in the present day where the media plays an influential role in creating awareness. The latter is usually framed by misinformation that is underpinned by an agenda or prejudiced ideology. Unfortunately, this message of blame and hatred now resonates with the virus itself, with race becoming the core of the perceived problem. To write this is ridiculous in itself as we should be focusing on how we can help mitigate and alleviate the impacts of the disease. Yet, many of the actions and stories of discrimination which have surfaced, show how many are influenced by the rhetoric of condemnation instead of compassion.

In times of catastrophe, humanity should be able to stand together in solidarity, not question and blame one another for being the acclaimed ‘instigators’. Understandably, fear and concern are evident globally, but once again, it is not a justification to capitalise on anti-Chinese sentiment and radicalise people’s concerns. There is a dissimilarity between containing the virus with suitable measures and overtly stating that the country ‘received what it was asking for’. I don’t think anybody in the world, regardless of cultural barriers, wishes for these misfortunes to happen, especially when considering the Chinese New Year celebrations that coincided with the outbreak. Singling out every individual of Chinese descent and labelling them as ‘diseased’ or ‘dangerous’, is an extreme distortion of reality. Those who have chosen to speak and act critically, have associated these outcomes with the fate of the Chinese, somewhat warranting that they are undeserving of support. This shifting of blame does not provide a cure but spreads the disease even further through attitudes that become untreatable themselves.

Pigment and race have renewed racial intolerances that were already harbouring, with the virus becoming a reason to irrationally bring these fears into play. There is a difference between rational action and being outright offensive as a reason for ‘protecting’ oneself. The “Yellow Alert” headline in France by the regional newspaper Le Courrier Picard and the trending hashtag “I am not a virus”, are merely some other instances of how backlash has riddled the Asian community with newfound fears of marginalisation. Although these were a few months back, these are subtle but important examples of how racist sentiment can override logic and most importantly, empathy. Unfortunately, personal experience is rarely treated as concrete or serious when it should be. Emotions are viewed through a lens of subjectivity, which gives the excuse for others to classify them as unevidenced when the experiences themselves should be enough to be valid. Feelings are challenging to explain analytically but despite us all having different difficulties, pain and loss are all universal modes we have felt. However, this has been overridden by a sense of ‘difference’ and ‘the other’, which has become a common denominator amongst racists for enforcing this idea of us versus them.

Above all, I think it’s important to distinguish that disease outbreaks are capable of happening anywhere. For instance, new research evidence suggests that New York’s outbreak may have originated from Europe instead, challenging the misjudgement that the Chinese are ‘diseased carriers’ who should face full accountability. It is a myth that they are reserved and will only affect less technologically prepared countries. It is a myth that the colour of one’s skin is a representation of their inferiority or incapability. But it is a fact that this is a humanitarian crisis, one where its people who are affected should be treated with solace, understanding and most significantly, respect. Misinformation does not inform but threatens the accuracy of the situation. The point is that those of Chinese descent, or whoever for that matter, should not be treated with such a sickening mindset. Hatred perpetuates and inspires xenophobic standards that can only act as a further blanket of insecurity. This conceals those from the fact that blaming others does not fix or soothe our fears — it compels a wider audience to accept false beliefs of difference in regards to other cultures.

I know that this is only an opinion, but I encourage you to keep this in mind especially in a time of struggle for those affected and uncertainty for the future. Above all, Covid-19 should not be weaponized to induce panic and justify prejudiced assumptions. Not only that, but the fact that this Sinophobia is an issue, should make us question as a whole society, what kind of progress we are making if these attitudes are still withheld in people’s heads, only waiting to be cultivated when disaster strikes?