Orientalism and the Yellow Peril: a Brief Look into the Cornerstone of Racism Against Asians in America

In Edward Said’s first chapter of Orientalism, “Latent and Manifest Orientalism,” the emergence of the Oriental culture–a cumulative impression of the East projected by the West–is delineated and broken down to assist scholars and Asians and non-Asians alike in critiquing the harmful and warped iteration of Asian culture. The Yellow Peril is an extension of Orientalism, as it projected a prejudiced characterization of Asians, misleading the Western public to believe that Asians were foreigners who posed a threat to Western ideals, cultures, and the economy. In the name of capitalism, the exploitation of Asian immigrant labor has had astronomically harmful effects on the politicized development of race relations, labor ideologies, and immigration legislation alike in America.

The study of history, culture, and academia in Western countries have revolved around Eurocentric ideologies and the white perspective, allowing for the portrayals of Eastern and non-white cultures to be taken into the hands of European scholars to formulate impressions of what these cultures consist of, and what they represent. Said’s critique of Orientalism addresses the relativity of Oriental studies, as the sector is, after all, a mere “school of interpretation” of what Eastern culture is, rather than being a school of true fact, involving the input of Eastern scholars who practice and live the Oriental culture (Said, 1978, p. 203). According to Said, because Orientalism is an imposed product of political force, all Europeans who have contributed or referred to the concept of Orientalism are inherently racist, imperialistic, and ethnocentric (Said, 1978, p. 204). Unfortunately, as aforementioned, the study of history, culture, and academia have been so heavily influenced by Eurocentric ideologies and standards that the Orient has stood to be a reference point for European and white Americans idealizing westward expansion, capitalistic gain, and the idea of superiority on the basis of nativism.

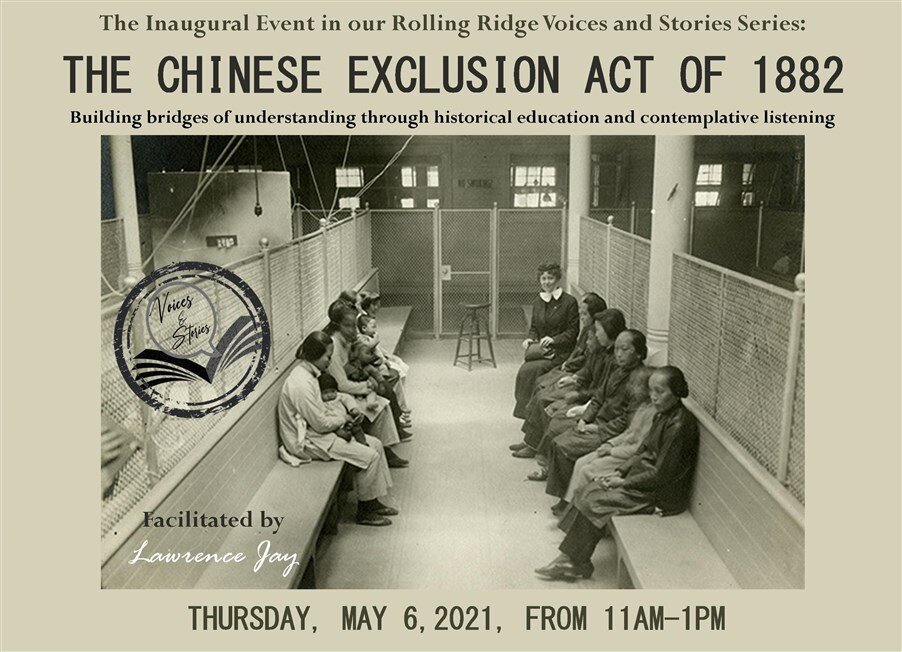

Photo credit: rollingridge.org

Because hate, defensiveness, and superiority coincide with the fear of what one does not know, anti-Asian violence and hate crimes have occurred on multiple occasions in America, and are a direct result of Orientalism’s widespread influence. In 1870, the exponential growth of Chinese migration to California in search of jobs as an industrial revolution ensued. In turn, the 1867 Anti-Chinese Union pledged to avoid employing the Chinese, and the union would later be absorbed into the Workingman’s Party of California within the next year. This party would rally and fight for the rights of the white laborer, particularly the Irish laborer, who was threatened by the affordable and subservient labor provided by Chinese coolies who would “defy the law… and utterly disregard all the laws of health, decency and, morality” (Okihiro, 1994, p. 35). This impression of Asians, in this particular instance, the Chinese, was derived from a mere impression of their people and culture was motivated by the fears perpetuated by job loss among the white working class. This can be identified as an effect of the Yellow Peril, which is known to represent a threat posed by Easterners, whether they are of South Asian, Southeast, or East Asia descent. The threat was undoubtedly thrust onto the overarching American impression of Eastern immigrants by the constant wedge driven between the white working class and Asian immigrant laborers by factory owners and workplace CEOs on both the East and West coasts of America.

The Yellow Peril was further imposed by the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which resulted in ethnic antagonism–or the outward acts of violence and mistreatment of subordinated peoples based on their ethnicity–and drove many Chinese workers from their jobs in agriculture and railroad construction simply due to the notion that they were a population that possessed all the “social vices,” with no regard for the freedoms and liberties of America’s culture, and with souls that resembled that of a “heathen” according to University of California, Berkeley professor, historian, and ethnographer Ronald Takaki in his narrative history novel Strangers from a Different Shore (p. 101). Orientalism and the Yellow Peril go hand in hand as they both derive from a white, ethnocentric viewpoint, and are perpetuated by Western capitalists seeking immigrant workers for two reasons: cheap labor costs and the redirection of the blame from CEOs to Asian workers when the white working-class ultimately loses their jobs.

As a result of the prioritization of capitalism upheld by the West, labor ideologies have largely circumvented the notion that the progress of civilization also meant the expansion westward to accommodate for new modes of production and agriculture, thus leading to widening trade opportunities. This ideology of productivity equals expansion and thus exploitation has had a direct impact on the culture surrounding labor in the 19th and 20th centuries. “Get labor first… and capital will follow” was the mantra sugar planters Hawaii followed that played an integral role in the arrangement of the 1875 Reciprocity Treaty which allowed for the exportation of sugar from the islands to the mainland (Takaki, 1989, p. 24). The hiring of Chinese laborers soon followed in a calculated manner, taking advantage of the less fortunate situations they may have been in in their homelands due to war and political turmoil, only to pay them low wages and pit them against white workers and native Hawaiian laborers.

On the east coast, the emergence of tensions between a dual economy in the South and traditional economy in the North displaced independent white laborers and artisans, and the Civil War’s push for monopoly capitalism encouraged the exploitation of racial minorities, as they were seen “as tools they used to undermine the white small producers and proletariat,” according to Professor Emeritus of Sociology and Ethnic Studies, Edna Bonacich in her academic paper, Labor Immigration Under Capitalism: Asian Workers in the United States Before World War II (Bonacich, 1984, p. 177). Immigrants who were racial minorities were more likely to be targeted by contract laborers and capitalists hungry for money and power, as they were more financially vulnerable and politically torn after coming from homelands that held ideological turmoil. Unlike the Irish laborers who were disadvantaged due to the Great Famine in 1848 but possessed white skin, Asian immigrants wore a “racial uniform,” and looked distinctively different from white immigrants (Takaki, 1989, p. 13). This racial uniform automatically allowed for the concept of the Yellow Peril to be associated with them, which would directly contribute to the racial tensions Asian immigrants faced, and the immigration legislation arranged in accordance to the fear of Asian laborers “stealing” the jobs of native and immigrant white laborers. When the development of the United States is highly regarded and veterans and white folk are repeatedly accredited for the country’s success, people of color are hardly ever granted recognition despite their ancestors quite literally building this country from the ground up.

The immigration legislation implemented throughout the 19th and 20th centuries was contradictory, especially as American contract laborers, factory owners, and sugar planters were initially all for the recruitment of Asian immigrant labor. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 was put into order because “the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities within the territory…”, which directly calls back to the fear of the unknown and unfamiliar to white immigrants and white “native” Americans, and plays into the narrative of the Yellow Peril’s extent (Chinese Exclusion Act, 1882, p. 58). In the informal Gentleman’s Agreement of 1908, Japan agreed to restrain emigration to the United States, while America agreed to neither encourage nor ban Japanese immigration. Despite finding loopholes in the system, Japanese strikers who demanded higher wages as there was low availability of Japanese labor were made an example for incoming Filipino workers (Takaki, 1989, p. 27). This chain of events relates to Orientalism, as the school of interpretation was used to uplift and uphold the supremacy of European culture, feeding into the superiority complex contract laborers beheld, justifying their act of using one ethnic group to threaten the job security of another. Orientalism and the Yellow Peril have fed into the preexisting fear of the other and the unknown, so much so that by the time the Civil Rights Act of 1870 was passed, the United States had collected five million dollars in taxes from the Chinese alone (Takaki, 1989, p. 82), and that’s not to mention the other countless imposed fines and naturalization restriction Asian immigrants faced.

The relationship between immigration legislation and labor ideologies imposed by America onto Asian immigrants has caused deep harm and trauma not only within each racial group but between them, instigating sour race relations that would last for decades. As aforementioned, the importation of Asian laborers and immigrants often came from the need to put the Asian workers already employed in their place, to prevent strikers from banding together against their employers to demand more money, or worse yet, to distract the white working class from the actual people at fault for their job losses: their employers, not the Asian immigrants who were filling their jobs for lower costs. Following the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, plantation and former slave owners complained that Africans who were once slaves were no longer interested in agricultural work, which is where the introduction of Chinese labor came in handy.

For the first time, the Chinese entered a biracial society composed of both Black and white people in the South instead of a predominantly white one, vastly different from the Hawaiian natives they had once encountered. Not only were the Chinese were seen as accessible, cheap labor, they were also seen as “models” for Black workers. Below the Mason Dixon line, their worth was once again compared to that of a group of people they were pitted against (Takaki, 1989, p. 94). This would in turn start a domino effect of high tensions and misconstrued understandings between Black and Asian people in America. According to Gary Okihiro’s Is Yellow Black or White?, African and Asian laborers in the western world were similar in a sense that they both played integral roles in the “maintenance of white supremacy,” thus qualifying each racial group’s hardships on the basis of their exploitation in relation to those who exploited them, rather than on the basis of who experienced worse.

In addition, there were (and still are) instances of racial prejudice and tensions between Asians and white Americans. Sansei, or third-generation Japanese Americans, have reflected on their upbringing and their impression of their place in society, claiming that “they felt no differently than non-Japanese, but they still felt prejudice toward Japanese (including themselves)” according to Wendy Ng’s “The Collective Memories of Communities.” South Asians were deemed to be the “spectre of a new ‘Yellow Peril’” in the eyes of the white working class, and were deemed a threat due to their darker, more defined features (Takaki, 1989, p. 297). The harmful rhetoric of Asian workers being the “model” for Black and white workers alike enforced a deeper, more harmful impression of Asians as the model minority: a more well-tempered group than those who possessed darker skin, but a qualified, more exploitable group that put white workers at risk of losing their jobs.

Not only did Asians suffer from racial tensions with Black Americans, white Americans, and white immigrants, but they also faced interethnic tensions. When Japanese immigrants in America were sought out to be representatives for Japan, there was a rising nationalist ideology driven by the Meiji Restoration. The Japanese compared their status to that of the Chinese, hoping to avoid their “failure” (Takaki, 1989, p. 46). In 1898, 300 Japanese laborers taunted a hundred Chinese workers, forcing them from their camp and their jobs at the Spreckelsville Plantation on Maui, which is just one of the instances where Asian ethnic groups collided in the name of capitalism, and under the warped iteration of Asian culture defined by Orientalism and the Yellow Peril.

Furthermore, the widespread act of referencing Orientalism and fostering the untrue fear-driven Yellow Peril has ultimately affected the course of the Asian identity and experience in America, whether it is one of immigrant or naturalized status. Labor ideologies, immigration legislation, and racial relations have all been shaped in accordance with Orientalism and the Yellow Peril, but it is important to note that Orientalism and the Yellow Peril were shaped in accordance with the white perspective. Asian immigrants were simply a pawn in the grand scheme of capitalism, westward expansion, and white America in general: an intricately fabricated falsehood that has caused not only Asian Americans but all people of color immense harm.